doi: 10.56294/nds2024118

ORIGINAL

Resilience and nursing intervention in adolescents from an educational institution in a vulnerable area of Lima

Resiliencia y la intervención de enfermería en adolescentes de una institución educativa en zona vulnerable de Lima

Olmar

Reymer Tumbillo Machacca1 ![]() , Juan Alberto Almirón Cuentas1

, Juan Alberto Almirón Cuentas1 ![]() , Yaneth Fernández-Collado2, Freddy Ednildon

Bautista-Vanegas3

, Yaneth Fernández-Collado2, Freddy Ednildon

Bautista-Vanegas3 ![]() *,

Pablo Carías4

*,

Pablo Carías4 ![]()

1Universidad Peruana Unión. Perú.

2Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa. Perú.

3Kliniken Beelitz GmbH Neurologische Rehabilitationsklinik. Beelitz Heilstätten, Brandenburg, Germany.

4Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Departamento de Cirugía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras. Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

Cite as: Tumbillo Machacca OR, Almirón Cuentas JA, Fernández-Collado Y, Bautista-Vanegas FE, Carías P. Resilience and nursing intervention in adolescents from an educational institution in a vulnerable area of Lima. Nursing Depths Series. 2024; 3:118. https://doi.org/10.56294/nds2024118

Submitted: 02-07-2023 Revised: 01-10-2023 Accepted: 13-01-2024 Published: 15-01-2024

Editor: Dra.

Mileydis Cruz Quevedo ![]()

Corresponding Author: Freddy Ednildon Bautista-Vanegas *

ABSTRACT

Relationships within the family are very important during adolescence, as they allow young people to develop skills and behaviors that improve their resilience. The objective of this research is to determine the resilience and nursing intervention in adolescents at an educational institution in a vulnerable area of Lima. This is a quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional study with a population of 571 adolescents who responded to a questionnaire on sociodemographic aspects and the Conno-Davidson resilience scale. The results show that 157 (27,5 %) of the adolescents have low resilience, 301 (52,7 %) have medium resilience, and 113 (19,8 %) have high resilience. In conclusion, family intervention should be taken into account in order to identify factors that put adolescents at risk in their early development.

Keywords: Resilience; Mental Healt; Family Health.

RESUMEN

La relación dentro de la familia es muy importante en la adolescencia, puesto a que le va a permitir desarrollar capacidades y conductas que mejoren su resiliencia, por lo que el objetivo de investigación es determinar la resiliencia y la intervención de enfermería en adolescentes de una institución educativa en zona vulnerable de Lima. Es un estudio cuantitativo, descriptivo y transversal, con una población de 571 adolescentes que respondieron un cuestionario de aspectos sociodemográficos y la escala de resiliencia de Conno-Davidson. En sus resultados, 157 (27,5 %) de los adolescentes tienen una baja resiliencia, 301 (52,7 %) resiliencia media y 113 (19,8 %) una alta resiliencia. En conclusión, se debe tener en cuenta la intervención en la familia para poder identificar factores que pongan en riesgo al adolescente en su desarrollo temprano.

Palabras clave: Resiliencia; Salud Mental; Salud Familiar.

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) during confinement made it a good coping method to use our personal and emotional resources to try to control it, making it a very difficult situation to deal with. concerns and uncertainty have particularly affected the adolescent population, as they were not prepared,(1) given that the causative agent SARS-CoV-2 mainly affected young people, who felt the direct and indirect consequences of the preventive measures against the virus. These included measures adopted by governments, such as mandatory social lockdowns and the closure of public establishments to prevent the spread of the virus, all of which led to multiple restrictions on human activities and physical interactions and a growing recognition of the effects on the mental health of children and adolescents.(2)

More importantly, resilience is not a state but a highly dynamic process characterized by fluctuating protective factors that are used to one's advantage to mitigate risks in different circumstances and at different times in the life stage.(3)

Among the different population groups affected, adolescents showed great emotional vulnerability, as pandemic restrictions added significant suffering that hindered their relationships with their peer group, a fundamental factor for socio-emotional development.(4) Despite the existing difficulties, human beings tend to adapt to stressful life situations, such as COVID-19.(5)

Therefore, as in the adult population, adolescents are expected to adapt to the pandemic;(6) since the beginning of the pandemic, multiple studies have been published on its impact on mental health, especially in school-age children, who have shown an increase in internalization problems, such as anxiety and depression; and externalizing problems, such as anger and lower life satisfaction, causing their level of resilience to vary according to the individual's state.(7) As a result, due to lockdown, young people are at greater risk of developing mental health problems than adults.(8)

Among young people and children, physical isolation from classmates, friends, and other important adults leads to chronic loneliness, which in turn leads to an unsafe family environment that is physically, psychologically, or sexually abusive, generating mental health problems such as increased anxiety, because they may worry that they or a loved one will become infected, or they may worry about the future of the world.(9)

In North America, a study in the United States of 225 refugee adolescents in Massachusetts showed that the proportion of anxiety and depression above the threshold was 34,2 % and 24 %, revealing that resilience was inversely associated with both anxiety and depression, given that the highest resilience scores had a significantly lower risk of anxiety and depression.(10) Another study in Mexico involving 116 students showed that 13 adolescents had a medium level of resilience, compared to 103 adolescents who had a high level of resilience, and 85 % of adolescents had a high percentage of internal protective factors, meaning that their levels of hope for the future were high. Of these, 75 % had a high level of resilience with respect to external protective factors, allowing us to infer that they have resilient characteristics favored by their personal structure.(11)

In Europe, a study conducted in Switzerland with 317 students participating at two points in time (before and during the pandemic) revealed that high mental health problems and high levels of protective factors at both points in time could be considered the resilient group, which was 21 % before the pandemic and 26,3 % during the pandemic. The so-called non-resilient group before the pandemic was 42,8 % and during the pandemic was 37,3 %, highlighting the importance of research, health promotion, and specific interventions in terms of resilience.(12)

A study in Spain of 476 adolescents (50 % from Spain and 50 % from Ecuador) revealed that 20,4 % experienced a stressful life event during lockdown, the most frequent being the loss of someone close to them, 21,4 % had a physical health problem prior to the pandemic, and 12,6 % had a mental health problem, showing that adolescents in Ecuador had experienced more stressful life events than those in Spain. Resilience can cushion the blow, reducing the levels of anxiety, depression, and stress that arose during lockdown. An adjustment to adolescence can help with early detection, facilitating both the prevention of future psychological problems and the development of programs that seek to enhance adolescents' well-being and develop their ability to cope with adverse situations.(13)

In South America, in Ecuador, 77 students revealed that 62 % of students rated their resilience as high to average, while 38 % rated it as low, with women rating slightly above average at 66 % between high and average, showing that students can make judgments related to their own possibilities and their connection to their environment.(14)

A study conducted in Peru on 93 students in Puerto Maldonado revealed that 43 % have a moderate level of resilience, 23,7 % have a high level, 14 % had a low level, and 8,6 % had a very low level, indicating that resilient students are characterized by having partially developed the necessary skills to overcome difficulties and adapt to risky situations they encounter.(15) Another study in Lima, involving 141 adolescents between the ages of 11 and 17, revealed that 16,3 % have high resilience, 34,7 % have moderate resilience, and 48,9 % have low resilience, evidencing that the formation of resilience is due to the interaction of various factors such as constitutional or genetic, psychological, and social factors that are ly involved in it.(16)

Therefore, the objective of this research is to determine the resilience and nursing intervention in adolescents from an educational institution in a vulnerable area of Lima.

METHOD

Research type and design

According to the properties of the study, it is quantitative, with a descriptive-transversal methodology.(17)

Population

The population consists of a total of 571 adolescent participants from an educational institution.

Inclusion Criteria

· Participants who are regularly enrolled.

· Participants between 10 and 18 years of age.

· Participants who agree to participate and whose parents authorize their participation in the study.

Technique and Instrument

The technique used was a survey, which was conducted using a Google form to collect data using the APGAR family questionnaire and the Connor Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC).

The Connor Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) assesses 25 items distributed across five dimensions (persistence, tenacity, self-efficacy, control under pressure, adaptability and resilience, control and purpose, and spirituality), structured on a Likert scale where "0 = absolutely not," "1 = rarely," "2 = sometimes," "3 = often," and "4 = almost always." The final score ranges from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating greater resilience in the adolescent.(18)

The instrument was validated using the Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin sample adequacy test, obtaining a coefficient of 0,968 (KMO > 0,6), and Bartlett's sphericity test yielded significant results (X2approx. = 26308,933; gl =300; p = 0,000).

The reliability of the instrument was assessed using Cronbach's alpha, obtaining a score of 0,989 (α > 0,6) for the 25 items of the instrument.

Place and Application of the Instrument

In order to conduct the survey, prior coordination was made with the school administration to obtain the necessary permissions for the study and to provide information about the topic to be addressed.

RESULTS

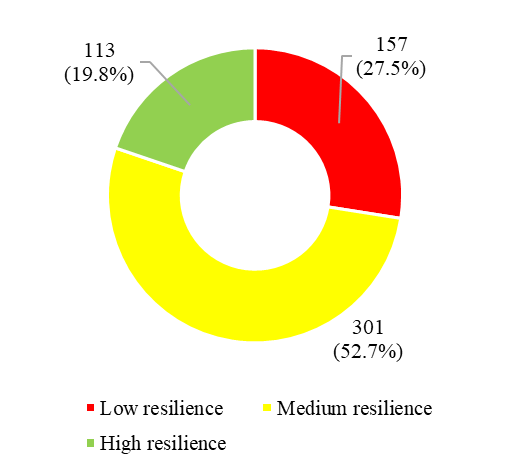

Figure 1. Resilience in adolescents at an educational institution in a vulnerable area of Lima

Figure 1 shows that 27,5 % (n=157) of participants have low resilience, 52,7 % (n=301) have medium resilience, and 19,8 % (n=113) have high resilience.

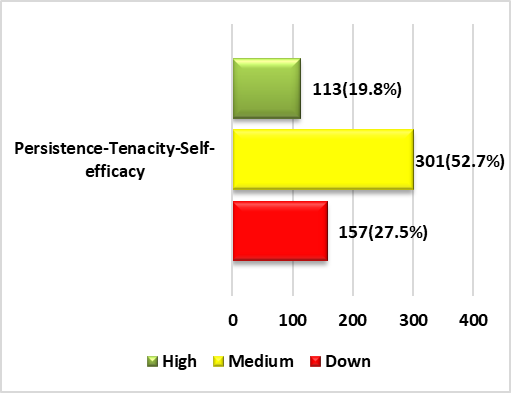

Figure 2. Resilience in its persistence-tenacity-self-efficacy dimension in adolescents from an educational institution in a vulnerable area of Lima

Figure 2 shows that 19,8 % (n=113) have high resilience in terms of persistence-tenacity-self-efficacy, 52,7 % (n=301) have medium resilience, and 27,5 % (n=157) have low resilience.

Figure 3. Resilience in terms of control under pressure among adolescents at an educational institution in a vulnerable area of Lima

In figure 3, we can see that 19,8 % (n=113) have high resilience with respect to their dimension of control under pressure, 52,7 % (n=301) have medium resilience, and 27,5 % (n=157) have low resilience.

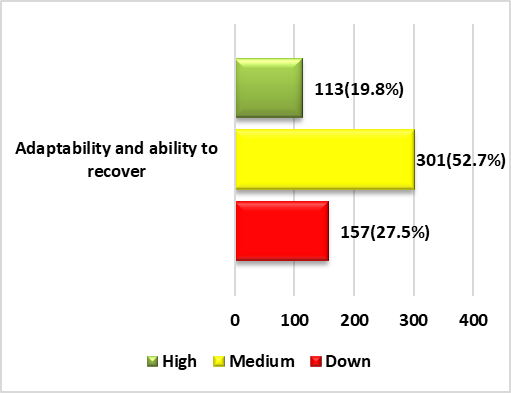

Figure 4. Resilience in terms of adaptation and ability to recover in adolescents from an educational institution in a vulnerable area of Lima

In figure 4, we can see that 19,8 % (n=113) have high resilience with respect to their adaptation dimension and ability to recover, 52,7 % (n=301) have medium resilience, and 27,5 % (n=157) have low resilience.

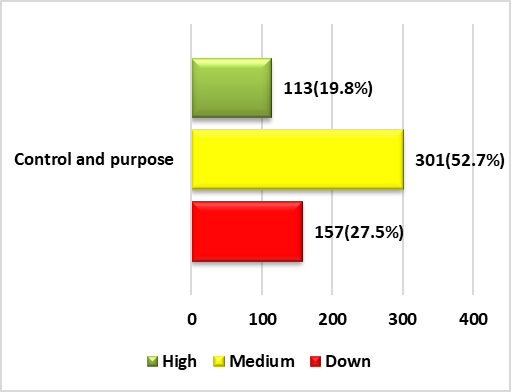

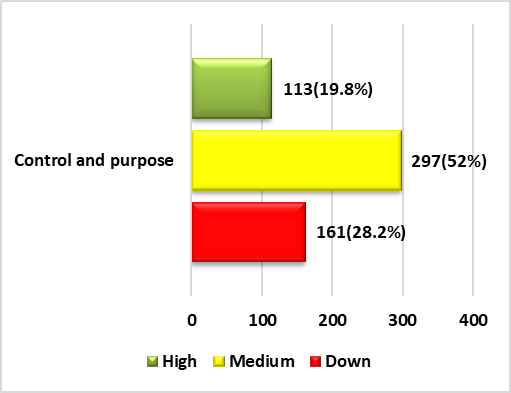

Figure 5. Resilience in terms of control and purpose among adolescents at an educational institution in a vulnerable area of Lima

Figure 5 shows that 19,8 % (n=113) of participants have high resilience in terms of control and purpose, 52,5 % (n=297) have medium resilience, and 28,2 % (n=161) have low resilience.

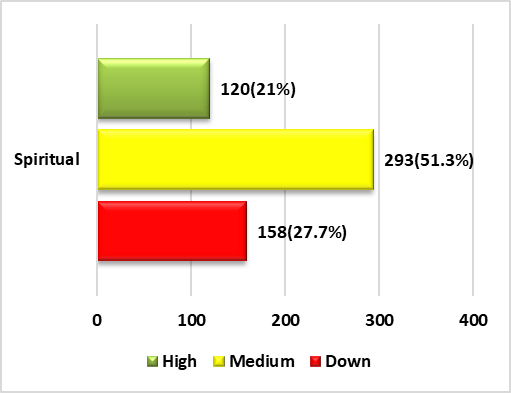

Figure 6. Resilience in its spirituality dimension in adolescents from an educational institution in a vulnerable area of Lima

Figure 6 shows that 21 % (n=10) of participants have high resilience in terms of spirituality, 51,3 % (n=293) have medium resilience, and 27,7 % (n=158) have low resilience.

DISCUSSION

In this research paper, we offer a perspective from the point of view of family health and mental health in adolescents in relation to their family environment.

The results show that adolescents have medium resilience. This is because intrafamilial relationships are increasingly scarce with adolescents today, given that factors such as empathy, sensitivity, love, and affection are not demonstrated as much by today's parents. In addition, adolescence is a stage in which emotional support from the family plays an important role in the adolescent's development, allowing them to function normally, express their abilities and skills, make positive decisions about themselves, and adapt to society, all of which will enable the adolescent to improve their levels of resilience.

In terms of its dimensions, we observe that there is a medium level of resilience, given that resilience in adolescents is very important for their academic, family, and social performance. However, factors that can decrease their levels of resilience, such as family dysfunction, problems within the home, separated parents, and consumption of harmful substances, among others, are factors that can compromise the development of adolescents' skills in their development in society. Therefore, a good family relationship helps adolescents to interpret all types of intra-family actions in a positive way, which also improves their adaptability in society and enables them to make good decisions that allow them to improve as people.

CONCLUSIONS

It is concluded that intervention in the family is necessary when risk factors compromise the adolescent's skill development.

It is concluded that counseling should be provided to parents on how to improve the development of their adolescent children's abilities, as this will help improve family interaction.

It is concluded that adolescents should be guided to expand their social and emotional knowledge to increase their levels of resilience.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. D. Ahorsu, C. Y. Lin, V. Imani, M. Saffari, M. D. Griffiths, and A. H. Pakpour, “The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation,” Int. J. Ment. Health Addict., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 1537–1545, Jun. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8.

2. U. Panchal et al., “The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review,” Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–27, 2021, doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w.

3. A. Stainton et al., “Resilience as a multimodal dynamic process,” Early Interv. Psychiatry, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 725–732, Aug. 2019, doi: 10.1111/eip.12726.

4. M. Orte, L. Ballester, and L. Nevot, “Factores de riesgo infanto-juveniles durante el confinamiento por COVID- 19: revisión de medidas de prevención familiar en España,” Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc., vol. 78, no. 1, pp. 205–236, 2020, doi: 10.4185/RLCS-2020-1475.

5. S. Chen and G. Bonanno, “Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: A resilience perspective.,” Psychol. Trauma Theory, Res. Pract. Policy, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 51–54, 2020, doi: 10.1037/tra0000685.

6. J. Espada, M. Orgilés, J. Piqueras, and A. Morales, “Las buenas prácticas en la atención psicológica infanto-juvenil ante el COVID-19,” Clinica y Salud, vol. 31, no. 2. Colegio Oficial de Psicologia de Madrid, pp. 109–113, Apr. 01, 2020, doi: 10.5093/CLYSA2020A14.

7. M. Sharma, A. Olsson, G. Banati, and P. Anthony, “Life in Lockdown: Child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID- 19,” 2021.

8. J. Deighton, S. Lereya, P. Casey, P. Patalay, N. Humphrey, and M. Wolpert, “Prevalence of mental health problems in schools: Poverty and other risk factors among 28 000 adolescents in England,” Br. J. Psychiatry, vol. 215, no. 3, pp. 565–567, Sep. 2019, doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.19.

9. M. Luijten et al., “The impact of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic on mental and social health of children and adolescents,” Qual. Life Res., vol. 30, no. 10, pp. 2795–2804, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02861-x.

10. K. Poudel, G. E. Chandler, C. S. Jacelon, B. Gautam, E. R. Bertone, and S. D. Hollon, “Resilience and anxiety or depression among resettled Bhutanese adults in the United States,” Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry, vol. 65, no. 6, pp. 496–506, Sep. 2019, doi: 10.1177/0020764019862312.

11. N. Moreno, A. Fajardo, A. González, A. Coronado, and J. Ricarurte, “Una mirada desde la resiliencia en adolescentes en contextos de conflicto armado,” SCIELO Rev. Investig. Psicol., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 57–72, 2019, Accessed: Dec. 08, 2022. http://www.scielo.org.bo/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2223-30322019000100005.

12. C. Janousch, F. Anyan, R. Morote, and O. Hjemdal, “Resilience patterns of Swiss adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a latent transition analysis,” Int. J. Adolesc. Youth, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 294–314, 2022, doi: 10.1080/02673843.2022.2091938.

13. S. Valero et al., “Emotional impact and resilience in adolescents in Spain and Ecuador during COVID-19: A cross-cultural study,” Rev. Psicol. Clin. con Ninos y Adolesc., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 29–36, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.21134/rpcna.2022.09.1.3.

14. M. Intriago, A. Tarazona, and I. Maitta, “La resiliencia en adolescentes con problemas de la conducta, con un enfoque de género en estudiantes del 10mo grado,” Rev. Sinapsis, vol. 1390, pp. 1–15, 2020, Accessed: Dec. 08, 2022. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7471226.

15. E. Estrada, “Inteligencia emocional y resiliencia en adolescentes de una institución educativa pública de Puerto Maldonado,” Cienc. y Desarro. Univ. Alas Peru., vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 27–35, 2020. http://revistas.uap.edu.pe/ojs/index.php/CYD/index.

16. D. Aldea, “Clima social familiar y resiliencia en adolescentes en situación de vulnerabilidad en Barrios Altos, Lima,” CASUS. Rev. Investig. y Casos en Salud, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 78–97, Nov. 2020, doi: 10.35626/casus.2.2020.282.

17. C. Fernández and P. Baptista, “Metodología de la Investigación.” p. 634, 2015. http://observatorio.epacartagena.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/metodologia-de-la-investigacion-sexta-edicion.compressed.pdf.

18. K. Connor and J. Davidson, “Manual Connor-Davidson resilience scale ( CD-RISC ),” vol. 18, no. 2. pp. 76–82, 2003, doi: 10.1002/da.10113