doi: 10.56294/nds2024119

ORIGINAL

Nursing care in the mental health of an underserved population in San Juan de Lurigancho

Cuidados de enfermería en la salud mental de una población desatendida en San Juan de Lurigancho

Paul Espiritu-Martinez1 ![]() , Rebeca Rocio Gomez Rosales2

, Rebeca Rocio Gomez Rosales2 ![]() , Blas Apaza Huanca3

, Blas Apaza Huanca3

1Universidad Nacional Autónoma Altoandina de Tarma, Junín, Perú.

2Hospital Infanto Juvenil Menino de Jesus, São Paulo, Brazil.

3Ministerio de Salud y Deportes, La Paz, Bolivia.

Cite as: Espiritu-Martinez P, Gomez Rosales RR, Apaza Huanca B. Nursing care in the mental health of an underserved population in San Juan de Lurigancho. Nursing Depths Series. 2024; 3:119. https://doi.org/10.56294/nds2024119

Submitted: 13-07-2023 Revised: 16-12-2023 Accepted: 19-04-2024 Published: 20-04-2024

Editor: Dra.

Mileydis Cruz Quevedo ![]()

ABSTRACT

Mental health worldwide was in crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic, facing situations that jeopardized their lives and that of their families. In response, people displayed negative factors such as depression, anxiety, and stress. Therefore, the research objective was to determine the mental health nursing care provided to an underserved population in San Juan de Lurigancho. This is a quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional study with 480 participants who completed a survey with sociodemographic data and the depression, anxiety, and stress scale. The results show that 39,8 % had normal depression, 13,5 % had mild depression, 27,1 % had moderate depression, 4,8 % had severe depression, and 14,8 % had extremely severe depression. In conclusion, coping strategies should be implemented for young people and adults to allow them to maintain their mental health in the face of risky situations that jeopardize their lives and that of their families.

Keywords: Mental Health; Vulnerability; Stress; Depression; Anxiety.

RESUMEN

La salud mental a nivel mundial se vio en crisis debido a la pandemia del COVID-19, ante situaciones que comprometían su vida y la de su familia, por lo que en respuesta las personas demostraban factores negativos como depresión, ansiedad y estrés, por lo que el objetivo de investigación es determinar los cuidados de enfermeria en la salud mental de una población desatendida en San Juan de Lurigancho. Es un estudio cuantitativo, descriptivo-transversal, con 480 participantes que respondieron una encuesta con datos sociodemográficos y la escala de depresión, ansiedad y estrés. En los resultados se observa, que el 39,8 % tiene depresión normal, 13,5 % depresión leve, 27,1 % depresión moderada, 4,8 % depresión severa y 14,8 % depresión extremadamente severa. En conclusión, se debe realizar estrategias de afrontamiento para las personas jóvenes y adultas, que les permita poder mantener su salud mental ante situaciones de riesgos que comprometan su vida y de su familia.

Palabras clave: Salud Mental; Vulnerabilidad; Estrés; Depresión; Ansiedad.

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), which began in Wuhan, China, has spread to many countries; causing the World Health Organization (WHO) Emergency Committee in January 2020 to classify the outbreak as a global health emergency based on the growing number of cases in China and other countries.(1) Due to its highly contagious nature of the virus and the increasing number of confirmed cases and deaths worldwide, not only the virus began to spread, but in turn negative feelings and thoughts that threatened the mental health of the population.(2) Moreover, during confinement, the possibility of psychological and mental problems increased, mainly due to the distance between people. In the absence of interpersonal communication, depressive and anxious disorders are more likely to occur or worsen.(3)

Findings in the United States, dated that people who exceed COVID-19 may have an increased risk of. likely to have these conditions as people with other pathologies.(4) In addition, during the pandemic, suicidal thoughts increased by between 8 % and 10 %, especially among young adults, rising to between 12,5 % and 14 %.(5)

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as: "A state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community".(6)

According to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), fear, worry, and stress are normal responses when we face uncertainty, the unknown, or situations of change or crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.(7)

The new infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, which has affected the entire world, has contributed to an increase in negative emotions such as fear, anxiety, stress, frustration, and vulnerability, causing uncertainty in many aspects of our lives, as there are no specific antiviral drugs or vaccines available.(8)

A study conducted in Cuba revealed that the COVID-19 outbreak was stressful for many people. Fear and anxiety resulting from lockdown were overwhelming and caused intense emotions in both adults and children. Given that those who showed a stronger stress response in this type of crisis are mostly more vulnerable populations.(9)

In Spain, a study conducted during lockdown involving 1 596 people living in 311 cities in 16 autonomous communities across the country found that age acts as a protective factor, with older people appearing to be less psychologically affected by the social and health crisis caused by the pandemic. They also indicate that people with lower incomes and less space per person in their homes are more vulnerable to the psychological impact of COVID-19.(10)

In Asia, a study in Singapore revealed an increase in negative emotions (anxiety, depression, and anger) and a decrease in positive emotions (happiness and satisfaction). This led to erratic behavior among people, which is a common phenomenon, as there is much speculation about how and how quickly the disease is transmitted, currently without a definitive treatment.(11)

In the study conducted in China, 1 210 respondents from 194 cities in China reported that 24,7 % of participants experienced moderate to severe psychological impact. Concluding that during the initial phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in China, more than half rated the psychological impact as moderate to severe, and about a third reported moderate to severe anxiety.(12)

In Ecuador, a study of 766 people found that around 8 % reported having been diagnosed with COVID-19 and 12,9 % experienced related symptoms. It indicated that 77,4 % had no mental health problems in the past and 87,6 % had no such problems during the pandemic. However, 41 % acknowledged experiencing greater psychological distress. Women and young adults were the most affected.(13)

In Peru, with 560 adolescents participating in the study at the secondary and university levels, 45,6 % felt the onset or increase of anxiety symptoms and 36,8 % felt depressive symptoms. It was concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic and associated factors such as social isolation generate symptoms that affect the mental health of adolescents, linked to anxiety and depressive disorders, with a higher prevalence in women.(14)

Therefore, the research objective is to determine the nursing care required for the mental health of an underserved population in San Juan de Lurigancho.

METHOD

Research type and design

The study is quantitative in nature and uses a descriptive, cross-sectional, non-experimental methodology.(15)

Population

The population consisted of a total of 480 participants aged between 18 and 60 years old.

Inclusion Criteria

· Participants who are of legal age

· Participants who have lived in the district of San Juan de Lurigancho for more than 1 year

· Participants who voluntarily agree to participate in the study

Technique and Instrument

The data collection technique was the survey in which the DASS-21 instrument is described.

The depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS-21) has three dimensions divided into 14 items each, and the dimensions are subdivided into indicators of 2 to 5 items. The depression dimension assesses devaluation of life, self-contempt, lack of interest or participation, hopelessness, dysphoria, anhedonia, and inertia. The anxiety dimension assesses situational anxiety, skeletal muscle effects, autonomic arousal, and the subjective experience of anxious affect. The stress dimension assesses agitation, impatience, difficulty relaxing, and nervous excitement. The response options are on a Likert scale where "0 = not at all," "1 = sometimes," "2 = most of the time," and "3 = all of the time." The higher the score, the more likely it is that the respondent's mental health has been compromised.(16)

The instrument was validated using the Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin test, obtaining a coefficient of 0,894 (KMO > 0,8), and Bartlett's sphericity test obtained significant results (Approx. X2= 7767,328; gl = 210; Sig.= 0,000).

The reliability of the instrument was assessed using Cronbach's alpha, obtaining a score of 0,944 (α > 0,8) for the 21 elements of the instrument, which allows us to determine that the instrument is reliable.

Place and Application of the Instrument

To carry out the study, we first coordinated with the head of each household in the district of San Juan de Lurigancho, where we explained the surveys to be conducted so that they would be aware of the research topic to be addressed.

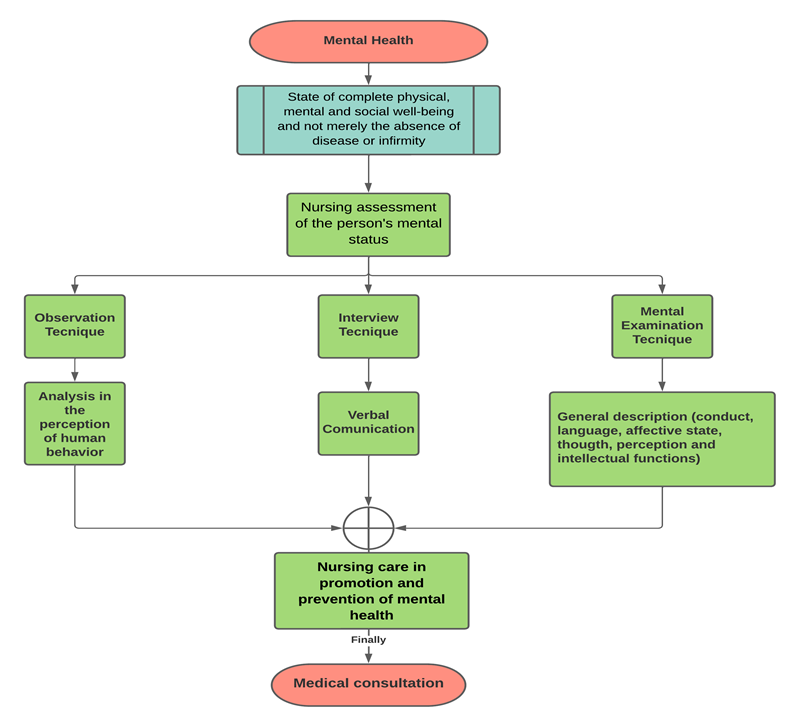

Figure 1. Flow chart of nursing intervention in mental health care

This flowchart describes the assessment carried out by mental health nursing professionals, which is performed using three techniques:

· Observation technique: This technique is used by nursing professionals as a resource to evaluate human behavior. In order to perform this technique, the observer must have an open attitude, free of prejudices, and use their senses to perceive the user's behavior as it is expressed.

· Interview technique: This technique is used by nursing professionals to obtain information through verbal communication, by means of the person's statements about their perceptions, ideas, beliefs, feelings, and actions.

· Mental examination technique: In this technique, the nursing professional will describe the person's mental functions as a result of observation and orderly and systematic exploration of signs and symptoms at a given moment, evaluating their appearance, behavior, language, affective state, thinking, perception, and intellectual functions.

Once the three procedures for assessing the person's mental health have been carried out, the nursing professional will promote and prevent factors that compromise mental health, and finally refer the person to a medical consultation to determine whether or not their mental health is impaired.

RESULTS

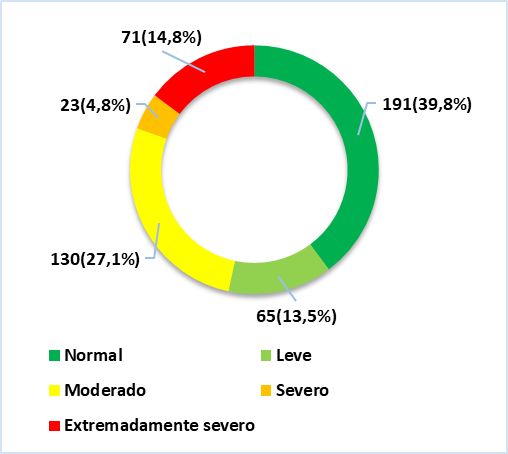

Figure 2. Depression in an underserved population in San Juan de Lurigancho

We can see in figure 2 that 39,8 % (n=191) of participants have a normal level of depression, 13,5 % (n=65) have mild depression, 27,1 % (n=130) have moderate depression, 4,8 % (n=23) have severe depression, and 14,8 % (n=71) have extremely severe depression.

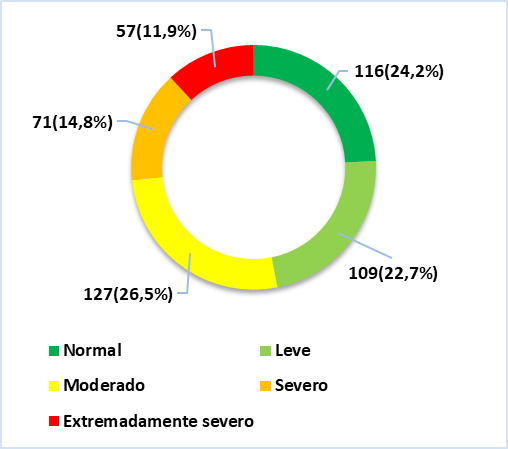

Figure 3. Anxiety in an underserved population in San Juan de Lurigancho

We can see in figure 3 that 24,2 %(n=116) of participants have a normal level of anxiety, 22,7 % (n=109) have mild anxiety, 26,5 % (n=127) have moderate anxiety, 14,8 % (n=71) have severe anxiety, and 11,9 % (n=57) have extremely severe anxiety.

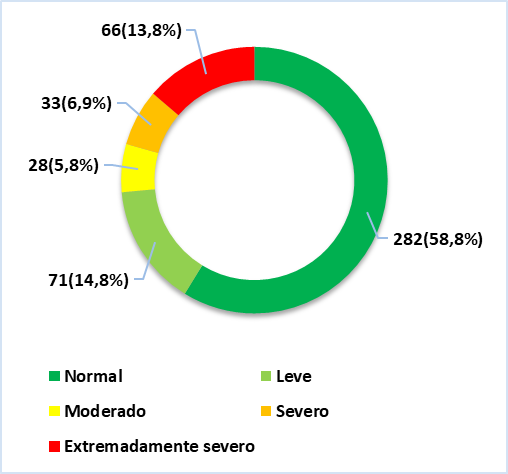

Figure 4. Stress in an underserved population in San Juan de Lurigancho

We can see in figure 4 that 58,8 %(n=282) of participants had normal stress levels, 14,8 % (n=71) had mild stress levels, 5,8 % (n=28) had moderate stress levels, 6,9 % (n=33) had severe stress levels, and 13,8 % (n=66) had extremely severe stress levels.

DISCUSSION

This study covers nursing care for the mental health of the population, with the aim of developing strategies to improve coping skills or styles for people whose mental health is vulnerable.

The results of the main variables, depression, anxiety, and stress, show that the variable with the most evidence of mental health impairment in the study population was anxiety. This is because, especially in young people and adults, they do not have the necessary information about the care that must be taken into account for their mental health, given that at higher levels of anxiety, we can have symptoms such as headaches, gastrointestinal pain, fatigue, mood swings, and insomnia. All of these factors that cause anxiety in a person are symptoms that indicate that the person is entering a state of somatization, whether situational or temporary, as a result of the disease and also due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition, many mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and stress have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, given that factors such as quarantine, social isolation from an infected family member, the death of a family member due to COVID-19, changes in routine, a sedentary lifestyle, melancholy, sadness, and fatigue are factors that have predisposed people to experience alterations in their mental state, making them vulnerable to any situation that compromises their well-being.

Therefore, it is important to develop measures to reduce or minimize depression, anxiety, and stress, since COVID-19 has generated psycho-emotional conflict in individuals, causing risks of mental disorders that can lead to depression, anxiety, or stress. Therefore, measures to protect people's mental health must be taken into account, given that there are multiple factors that make a person's mental state vulnerable.

CONCLUSIONS

It is concluded that motivational counseling should be provided to young people and adults through mental health promotion and prevention programs in situations that may compromise mental health.

It is concluded that health professionals should be trained in the early recognition of mental health problems in individuals.

This research will be beneficial for other scholars to develop on this topic, given that mental health interventions are sometimes scarce and thus minimize the risks caused by mental health disorders.

REFERENCES

1. Velavan T, Meyer C. The COVID-19 epidemic. Trop Med Int Health. 2020;25(3):278-80. doi:10.1111/tmi.13383.

2. Huarcaya J. Mental health considerations about the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2020;37(2):327-34. doi:10.17843/RPMESP.2020.372.5419.

3. Chunfeng X. A Novel approach of Consultation on 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19)-related psychological and Mental problems: Structured letter therapy. Psychiatry Investig. 2020;17(2):175-6. doi:10.30773/pi.2020.0047.

4. Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes J, Harrison P. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(2):130-40. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4.

5. O’Connor R, et al. Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. Br J Psychiatry. 2021;218(6):326-33. doi:10.1192/bjp.2020.212.

6. Organizacion Panamericana de la Salud. Salud Mental. OPS; 2013. Available: https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/31342/salud-mental-guia-promotor.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

7. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Salud Mental y COVID-19. OPS; 2020. Available: https://www.paho.org/es/salud-mental-covid-19.

8. Suárez A. La Salud Mental en Tiempos de la COVID-19. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2020;94(1):1-4. Available: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/biblioPublic/publicaciones/recursos_propios/resp/revista_cdrom/VOL94/EDITORIALES/RS94C_202010126.pdf.

9. Hernandez J. Impacto de la COVID-19 sobre la salud mental de las personas. Medicent Electron. 2020;24(1):578-94. Available: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/mdc/v24n3/1029-3043-mdc-24-03-578.pdf.

10. Parrado A, León J. COVID-19: Factores asociados al Malestar Emocional y Morbilidad Psíquica en población Española. Rev Española Salud Publica. 2020;94(8):1-16. Available: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/biblioPublic/publicaciones/recursos_propios/resp/revista_cdrom/VOL94/ORIGINALES/RS94C_202006058.pdf.

11. Ho C, Chee C, Ho R. Mental Health Strategies to Combat the Psychological Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Beyond Paranoia and Panic. Ann. 2020;49(3):155-60. Available: https://annals.edu.sg/pdf/49VolNo3Mar2020/V49N3p155.pdf.

12. Wang C, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051729.

13. Hermosa C, et al. Síntomas de depresión, ansiedad y estrés en la población general ecuatoriana durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Rev Ecuatoriana Neurol. 2021;30(2):40-7. doi:10.46997/revecuatneurol30200040.

14. Ñañez M, Lucas G, Gómez R, Sánchez R. El Covid-19 en la salud mental de los adolescentes en Lima Sur, Perú. Horiz la Cienc. 2021;12(22):219-31. doi:10.26490/uncp.horizonteciencia.2022.22.1081.

15. Fernández C, Baptista P. Metodología de la Investigación. 2015. Available: http://observatorio.epacartagena.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/metodologia-de-la-investigacion-sexta-edicion.compressed.pdf.

16. Lovibond A. Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21). 1995. Available: http://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/dass/Downloadfiles/Dass21.pdf.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Pablo Espíritu-Martínez, Rebeca Rocío Gómez Rosales, Blas Apaza Huanca.

Writing – original draft: Pablo Espíritu-Martínez, Rebeca Rocío Gómez Rosales, Blas Apaza Huanca.

Writing – review and editing: Paul Espiritu-Martinez, Rebeca Rocio Gomez Rosales, Blas Apaza Huanca.