doi: 10.56294/nds202219

ORIGINAL

Total family risk in families with children under 5 years old in a vulnerable area of North Lima

Riesgo familiar total de familias con infantes menores a 5 años de una zona vulnerable de Lima Norte

Jorge Arturo Zapana-Ruiz1 *, Susan Gutiérrez-Rodríguez2 *

1Universidad Tecnológica del Perú.

2Universidad Norbert Wiener.

Cite as: Zapana-Ruiz JA, Gutiérrez-Rodríguez S. Total family risk in families with children under 5 years old in a vulnerable area of North Lima. Nursing Depths Series. 2022; 1:19. https://doi.org/10.56294/nds202219

Submitted: 23-01-2022 Revised: 14-04-2022 Accepted: 02-07-2022 Published: 03-07-2022

Editor: Dra.

Mileydis Cruz Quevedo ![]()

Corresponding Author: Jorge Arturo Zapana-Ruiz *

ABSTRACT

Family risk is one of the probabilities in which adverse situations can occur within the family that can be witnessed during a family assessment, therefore, the research objective is to determine the total family risk of families with children under 5 years of age in a vulnerable area of North Lima. It is a quantitative, descriptive-cross-sectional study, with a total population made up of 140 heads of households with children under 5 years of age who answered a questionnaire on sociodemographic aspects and the total family risk instrument. The results show that 62,9 % (n = 88) of heads of household have a family at low risk, 27,1 % (n = 38) have threatened families, and 10 % (n = 14) have families at high risk. In conclusion, strengthening health professionals in terms of extramural work is very important because it allows them to identify if there is any risk that compromises the family, especially the infant, and to be able to act accordingly.

Keywords: Family; Family Relations; Public Health; Coronavirus.

RESUMEN

El riesgo familiar es una de las probabilidades en las que dentro de la familia pueden ocurrir situaciones adversas que se pueden presenciar durante una valoración familiar, por lo que, el objetivo de investigación es determinar el riesgo familiar total de familias con infantes menores 5 años de una zona vulnerable de Lima Norte. Es un estudio cuantitativo, descriptivo-transversal, con una población total conformada por 140 jefes de hogar con infantes menores de 5 años que respondieron un cuestionario de aspectos sociodemográficos y el instrumento de riesgo familiar total. En los resultados, se puede observar que, el 62,9 % (n=88) de los jefes de hogar tienen una familia con riesgo bajo, el 27,1 % (n=38) tienen familias amenazadas y 10 % (n=14) tienen familias con riesgo alto. En conclusión, el fortalecimiento de los profesionales de salud en cuanto a las labores extramurales es muy importante porque permite identificar si existe algún riesgo que comprometa a la familia sobre todo al infante y poder actuar de acuerdo a la situación.

Palabras clave: Familia; Relaciones Familiares; Salud Pública; Coronavirus.

INTRODUCTION

The new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has spread rapidly across the globe and was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in response to a health crisis that has so far left 511 107 390 people infected and 6 225 901 dead.(1,2) The COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect global populations in unprecedented ways. Families and individuals who make up these social and universal units have been particularly hard hit.(3)

COVID-19 poses a serious threat to the well-being of children and families due to challenges related to social disruption such as financial insecurity, the burden of care, and stress related to confinement (overcrowding, changes in structure and routine). The consequences of these difficulties are likely to be long-lasting, in part because of the ways in which contextual risk permeates the structures and processes of family systems.(4)

As such, family risks can have detrimental effects on a wide range of developmental and growth outcomes in children, especially during the early years of life. These factors may be due to a number of characteristics of family members, as well as the collective attributes of socioeconomic (family poverty, low parental education, or single-parent families), interpersonal aspects (family conflict, maltreatment, or abuse), critical life events (death or illness of significant others, frequent moves, or migration), and other risks, including parents (drug abuse or mental illness).(5)

Therefore, the current COVID-19 crisis has been particularly damaging and vulnerable for low-income families with young children. For this reason, most parents have had to deal with and manage painful difficulties in order to survive this pandemic crisis together with their young children.(6)

The family is currently undergoing a process of profound change due to the continuous global changes that have occurred in recent decades. These changes threaten structural, functional, and evolutionary stability, bringing about consequent changes in health and well-being patterns throughout the family life cycle.(7)

However, family structure experiences are important for child development because they influence children's care environments, including parenting levels and the economic resources available or invested in them, and the nature of their relationships with their caregivers.(8)

A study conducted in the United Kingdom observed that, among 11 000 study participants, low-risk families accounted for 57,6 %, high-risk families for 16,3 %, high-risk single-parent families for 24 %, and ethnic minority families for 2,1 %. Within their offspring, we identified five different risk configurations: low-risk families (62 %), low-risk families without children (15,1 %), moderate-risk single-parent families (10,1 %), moderate-risk large families (8,9 %), and high socioeconomic and high psychosocial risk (4 %). However, we find that social support can open up new opportunities, especially in terms of education and employment, but also new risks and potentially a growing marginalization of the most vulnerable families.(9)

A study conducted in Peru with 112 parents used several instruments, including the "RFT 5-33." The findings showed that threatened families were more prevalent in terms of total family risk (58 %) and also in terms of factors (≥72,3 %). It concluded that threatened families were more prevalent in terms of family risk and its dimensions.(10)

Another study conducted in Peru with 336 participants found that 61,6 % of families were at low risk, 23,8 % were at threatened family risk, and 14,6 % were at high family risk. It concluded that family health programs should be strengthened and complemented with comprehensive actions that can identify risks within the family.(11)

Therefore, the research objective is to determine the total family risk of families with children under 5 years of age in a vulnerable area of northern Lima.

METHOD

Research type and design

The study is quantitative in nature and uses a descriptive, cross-sectional, non-experimental methodology.(12)

Population

The total population consists of 140 heads of households with children under 5 years of age.

Inclusion Criteria

· Participants with children under 5 years of age.

· Participants who are heads of households over the age of 20.

· Participants who voluntarily agree to participate in the study.

Technique and Instrument

The data collection technique was a survey, which included sociodemographic aspects and the Total Family Risk (RFT5:33) instrument.

The RFT5:33 is an instrument consisting of 33 items distributed across five dimensions (psycho-affective conditions, health services and practices, housing and neighborhood conditions, socioeconomic status, and child care). The alternatives are based on a Likert scale where the response options are dichotomous, with "1 = presence of risk" and "0 = absence of risk." The final score ranges from 0 to 33 points. The assessment scale ranges from "0 to 4 points" for low family risk, "5 to 12 points" for families at risk, and "13 to 33 points" for high family risk. Therefore, the higher the score, the greater the family risk.(13)

The reliability of the instrument was determined using Cronbach's alpha statistical test, obtaining a score of 0,810 (α > 0,7), which makes the instrument reliable for the study.

Place and Application of the Instrument

Prior coordination was carried out with each head of household with children under 5 years of age, and they were given prior information so that they had the necessary knowledge about the study.

RESULTS

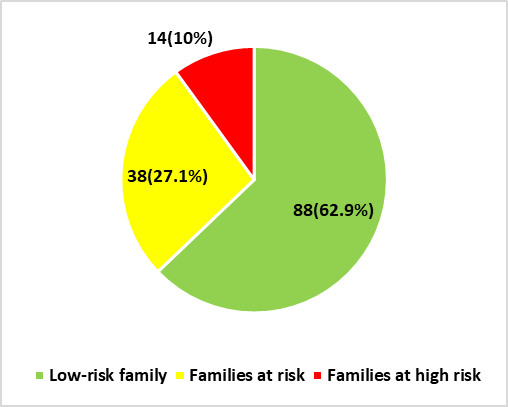

Figure 1. Total family risk of families with children under 5 years of age in a vulnerable area of northern Lima

Figure 1 shows that 62,9 % of participants have a low-risk family, 27,1 % have families at risk, and 10 % have high-risk families.

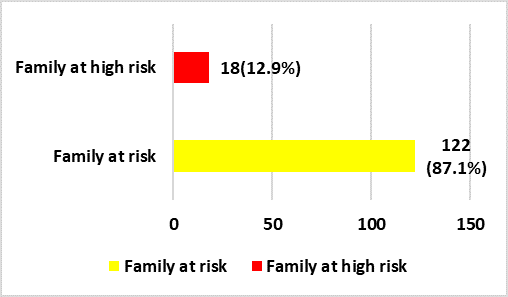

Figure 2. Total family risk in terms of psycho-affective conditions of families with children under 5 years of age in a vulnerable area of northern Lima

Figure 2 shows that, in relation to psycho-affective conditions, 12,9 % of participants have high-risk families and 87,1 % have families at risk.

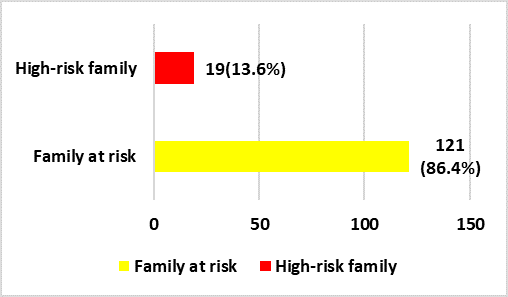

Figure 3. Total family risk in terms of health services and practices among families with children under 5 years of age in a vulnerable area of northern Lima

Figure 3 shows that, in terms of health services and practices, 13,6 % have high-risk families and 86,4 % are threatened.

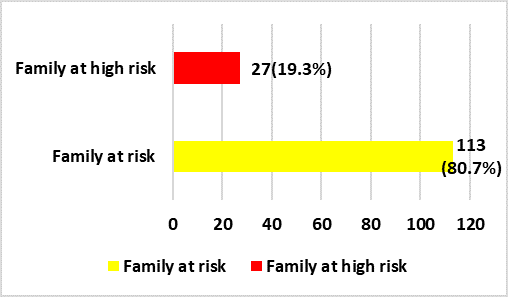

Figure 4. Total family risk in terms of housing and neighborhood conditions in households with families with children under 5 years of age in a vulnerable area of northern Lima

In figure 4, with regard to the housing and neighborhood conditions dimension in households, 19,3 % of participants have a high-risk family and 80,7 % have a threatened family.

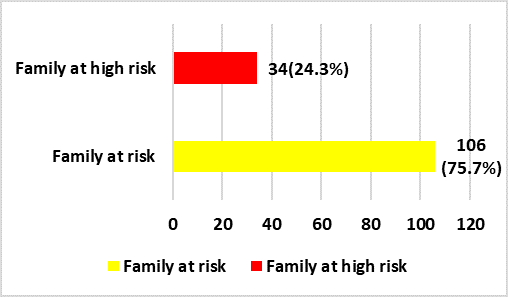

Figure 5. Total family risk in terms of socioeconomic status with children under 5 years of age in a vulnerable area of northern Lima

In figure 5, with regard to the socioeconomic dimension, 24,3 % of participants have a family at high risk and 75,7 % have a family at risk.

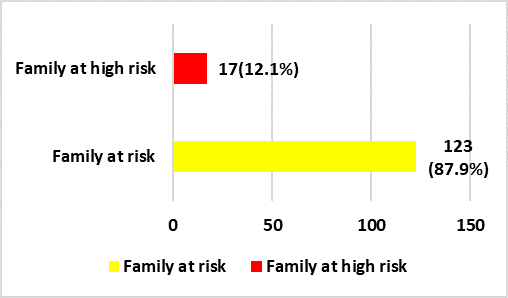

Figure 6. Total family risk in terms of child care with children under 5 years of age in a vulnerable area of northern Lima

In figure 6, with regard to the dimension of child care, 12,1 % of participants have families at high risk and 87,9 % have families at risk.

DISCUSSIONS

These times of health and economic crises caused by the pandemic and armed conflicts are plunging the planet into a scenario of shortages that will make it difficult to meet the basic needs of households. Families and their members will be affected, as will family dynamics. The health crisis and economic insecurity pose a serious threat to the well-being of children and families due to challenges related to social disruption, such as financial insecurity, the burden of care, and stress related to confinement (e.g., overcrowding, changes in structure and routine). The consequences of these difficulties are likely to be long-lasting, in part because of the ways in which contextual risk permeates the structures and processes of family systems.(14)

The tools used to mitigate the threat of economic precariousness and the harsh pandemic such as COVID-19 may well undermine child growth and development. These tools, such as social restrictions, lockdowns, and school closures, contribute to stress for parents and children and can become risk factors that threaten child growth and development and may compromise the Sustainable Development Goals.(15)

For these reasons, it is essential to assess the total family risk, which provides us with elements for a more accurate diagnosis of families and the risks they face. Hence, the objective of this study, which seeks to generate scientific evidence related to this line of research on family and child health. The implementation of policies to curb the spread of the pandemic has caused some disruptions in people's lives, such as separation from family and friends, food and medicine shortages, loss of income, social isolation due to quarantine or other social distancing programs, and school closures. The mental or emotional health of family members was affected, according to evidence reported in recent months. This also increased domestic violence and violence against children. Minors are experiencing a new normality.(16)

Finally, it should be noted that there are external factors that alter family dynamics, thereby altering their ability to adapt and protect themselves, thus making it impossible to guarantee the safety of family members. Children under the age of 5 tend to be the most vulnerable. Heads of households are often unprepared to meet the basic needs of their family members. Their employment status, educational level, and beliefs can negatively influence the health and development of the most vulnerable members of the family. Through primary health care, efforts should be redoubled in strategies aimed at family health care, in addition to work outside health facilities, such as home visits.(4)

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, extramural work by health professionals in the form of home visits should be strengthened in order to assess the family within the home, observe whether there are any risks to the infant, and act immediately.

Strategies should be implemented to strengthen family care in accordance with the jurisdiction of the health facility so that healthcare can be provided to those who need it.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. Organización Mundial de la Salud, “Coronavirus,” OMS, 2020. https://www.who.int/es/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1.

2. Johns Hopkins University, “Coronavirus Resource Center,” JHU, 2022. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

3. World Health Organization, “Managing family risk: a facilitator’s toolbox for empowering families to manage risk during COVID-19,” OMS, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/managing-family-risk-a-facilitator-s-toolbox-for-empowering-families-to-manage-risks-during-covid-19.

4. H. Prime, M. Wade, and D. Browne, “Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Am. Psychol., vol. 75, no. 5, pp. 631–643, 2020, doi: 10.1037/amp0000660.

5. H. Matta, R. Perez, E. Matta, and M. Yauri, “Total family risk in families who go to popular dining rooms in a vulnerable area of collique, comas,” Rev. ASTES, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 960–965, 2020. https://www.astesj.com/publications/ASTESJ_0505117.pdf.

6. M. Morelli et al., “Parents and Children During the COVID-19 Lockdown: The Influence of Parenting Distress and Parenting Self-Efficacy on Children’s Emotional Well-Being,” Front. Psychol., vol. 11, no. 11, p. 584645, 2020, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.584645.

7. C. Vélez, D. Betancurth, and C. Gallego, “Vista de Determinantes sociales de la salud y riesgo familiar en población de dos municipios de Caldas,” Rev. Investig. Andin., vol. 22, no. 40, pp. 153–164, 2020. https://revia.areandina.edu.co/index.php/IA/article/view/1592/1527.

8. F. Sticca, C. Wustmann, and O. Gasser, “Familial Risk Factors and Emotional Problems in Early Childhood: The Promotive and Protective Role of Children’s Self-Efficacy and Self-Concept,” Front. Psychol., vol. 11, no. 11, p. 547368, 2020, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.547368.

9. I. Schoon and G. Melis, “Intergenerational transmission of family adversity: Examining constellations of risk factors,” PLoS One, vol. 14, no. 4, p. e0214801, 2019, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214801.

10. L. Matta, “Riesgo y dinámica familiar en familias con menores de 5 años de una zona vulnerable de Comas,” Rev. Cuid. y Salud Pública, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 52–58, 2021, doi: 10.53684/csp.v1i1.13.

11. M. Guzman, “Riesgo Familiar Total durante la Pandemia por Coronavirus en Familias que reciben Asistencia Alimentaria en Carabayllo,” Rev. Investig. Agora, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 40–46, 2021. https://www.revistaagora.com/index.php/cieUMA/article/view/191/142.

12. C. Fernández and P. Baptista, “Metodología de la Investigación.” p. 634, 2015. http://observatorio.epacartagena.gov.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/metodologia-de-la-investigacion-sexta-edicion.compressed.pdf.

13. P. Amaya, “Instrumento de riesgo familiar total: RFT:5-33: manual. Aspectos teóricos, psicométricos, de estandarización y de aplicación del instrumento.” 2004. https://observatoriodefamilia.dnp.gov.co/Documents/Publicacionesexternas/Salud/3-manual-rft--pilar-a(salud).pdf.

14. M. Ekholuenetale, A. Wegbom, G. Tudeme, and A. Onikan, “Household factors associated with infant and under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa countries,” Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy, vol. 14, no. 10, pp. 1–15, 2020, doi: 10.1186/s40723-020-00075-1.

15. L. Arantes, C. Veloso, M. de Campos, J. Coelho, and G. Tarro, “The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child growth and development: a systematic review,” J. Pediatr. (Rio. J)., vol. 97, no. 4, pp. 369–377, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2020.08.008.

16. M. Ahmed, O. Ahmed, Z. Aibao, S. Hanbin, L. Siyu, and A. Ahmad, “Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated Psychological Problems,” Asian J. Psychiatr., vol. 51, no. 3, p. 102092, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092.

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Jorge Arturo Zapana-Ruiz, Susan Gutiérrez-Rodríguez.

Data curation: Jorge Arturo Zapana-Ruiz, Susan Gutiérrez-Rodríguez.

Formal analysis: Jorge Arturo Zapana-Ruiz, Susan Gutiérrez-Rodríguez.

Drafting - original draft: Jorge Arturo Zapana-Ruiz, Susan Gutiérrez-Rodríguez.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Jorge Arturo Zapana-Ruiz, Susan Gutiérrez-Rodríguez.