ORIGINAL

Experiences, Needs, and Challenges in the Clinical Care of Transgender, Transsexual, Transvestite, and Non-Binary People: A Nursing Perspective

Experiencias, necesidades y desafíos en la atención clínica de personas transgénero, transexuales, travestis y no binarias: un enfoque desde el personal de enfermería

Erika Silvia Stolino1

![]() *,

Carlos Jesús Canova-Barrios1,2

*,

Carlos Jesús Canova-Barrios1,2 ![]() *

*

1Universidad Nacional de Avellaneda. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

2Universidad de Ciencias Empresariales y Sociales (UCES). Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Argentina.

Cite as: Stolino ES, Canova-Barrios CJ. Experiences, Needs, and Challenges in the Clinical Care of Transgender, Transsexual, Transvestite, and Non-Binary People: A Nursing Perspective. Nursing Depths Series. 2023; 2:60. https://doi.org/10.56294/nds202360

Submitted: 01-05-2022 Revised: 15-09-2022 Accepted: 01-01-2023 Published: 02-01-2023

Editor: Dra.

Mileydis Cruz Quevedo ![]()

Corresponding author: Erika Silvia Stolino *

ABSTRACT

Objective: to explore the experiences, needs and challenges of the trans and non-binary population in relation to health care services, with a special focus on the care provided by nurses.

Method: descriptive, cross-sectional, quantitative study. A survey designed ex profeso was used. Forty people belonging to the trans and non-binary population who are in the Argentine public employment system and were incorporated after the enactment of the trans quota law participated.

Results: this study identified multiple barriers faced by transgender, transsexual, transvestite, and non-binary people in clinical care, particularly in the interaction with nursing staff. Among the main obstacles are discrimination, stigma, undignified treatment and lack of respect, as well as poor training of health personnel in specific regulations and sensitivity to gender diversity. The findings highlight the significant role of nursing staff in providing adequate and humanized care to this population.

Conclusions: it is essential to implement training programs in gender diversity, develop inclusive care protocols, and promote safe and respectful clinical environments that ensure equitable access to health services.

Keywords: Transgender Persons; Gender Identity; Quality of Health Care; Healthcare Disparities; Nursing.

RESUMEN

Objetivo: explorar las experiencias, necesidades y desafíos de la población Trans y No Binaria en relación con la atención en los servicios de salud, con un enfoque especial en la atención brindada por el personal de enfermería.

Método: estudio descriptivo, transversal y cuantitativo. Se utilizó una encuesta diseñada Ex Profeso. Participaron 40 personas pertenecientes a la población trans y no binaria que se encuentran en el sistema de empleo público argentino y fueron incorporadas después de la sanción de la ley de cupo trans.

Resultados: este estudio identificó múltiples barreras que enfrentan las personas transgénero, transexuales, travestis y no binarias en la atención clínica, particularmente en la interacción con el personal de enfermería. Entre los principales obstáculos se encuentran la discriminación, el estigma, el trato indigno y la falta de respeto, así como la escasa formación del personal de salud en normativas específicas y sensibilidad hacia la diversidad de género. Los hallazgos destacan el rol central del personal de enfermería en la provisión de una atención adecuada y humanizada a esta población.

Conclusiones: es fundamental implementar programas de capacitación en diversidad de género, desarrollar protocolos de atención inclusivos y promover entornos clínicos seguros y respetuosos que garanticen el acceso equitativo a los servicios de salud.

Palabras clave: Personas Transgénero; Identidad de Género; Calidad de la Atención de Salud; Disparidades en Atención de Salud; Enfermería.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the field of health has undergone a paradigm shift, characterized by the questioning of the hegemonic medical model and medicalization as a structural feature. This shift implies a transition toward a biopsychosocial model that promotes comprehensive and holistic care centered on the needs of the care recipient. This approach incorporates not only traditional and alternative practices, such as herbal medicine or accompaniment in reproductive processes, but also a human rights perspective that demands the recognition and respect of diversity, especially that which has been historically excluded.(1)

In this context, gender identity—present in the life cycle of every human being—takes on special relevance in health care. It is not limited to genitality or sexuality, but is an essential component of personal and social development. Despite regulatory advances, a binary and deterministic conception of gender persists in many societies, directly associating the sex assigned at birth with gender identity, which renders invisible and stigmatizes those who do not fit into this scheme.

Transvestites, transsexuals, transgender, and non-binary (TTT and NB) people are those whose gender identity does not correspond to the sex assigned at birth. This group continues to face severe rights violations, especially in the area of health.(2) Discrimination, pathologization, and social exclusion limit their access to quality health services.(3) In Argentina, although the Gender Identity Law(4) recognizes the right to self-perceived identity and guarantees free access to hormone treatments and surgical procedures for body modification, numerous reports indicate that discriminatory practices and negative experiences in clinical care persist.

According to a report by Fundación Huésped(5) seven out of ten transgender people are treated in the public health system. Before the law was passed, eight out of ten had experienced discrimination in this area; that proportion fell to three out of ten after its implementation. However, this reduction is not enough: stigma, dehumanizing treatment, and lack of training among health personnel, especially nurses, continue to affect the quality of care.

A study conducted by Zalazar et al.(6) with the aim of exploring the contextual, social, and individual barriers and facilitators to access to health care for transgender women in Buenos Aires identified contextual barriers (limited appointments and long waiting hours), social barriers (stigma, discrimination, and blame), and individual barriers (self-exclusion and anticipated stigma), and inclusive services as facilitators. The barriers identified lead to high rates of self-medication and silicone injections, which requires raising awareness among healthcare personnel.(7)

Given that nursing staff tend to have the longest and closest contact with patients during the care process, their role is key in building a respectful and inclusive healthcare experience.(8) However, many professionals still lack specific training in gender diversity, which reproduces discriminatory practices and reinforces exclusion.(9,10)

This study aims to explore the experiences, needs, and challenges of the trans and non-binary population in relation to healthcare services, with a special focus on the care provided by nursing staff. Through analysis, it seeks to contribute to knowledge about the barriers and facilitators of inclusive care, as well as to provide input for the development of more respectful, equitable, and human rights-centered practices.

METHOD

This was an observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study with a quantitative approach. Forty people working in a state-owned company in Buenos Aires, Argentina, agreed to participate voluntarily in the study. Workers from the TTT and NB groups who worked in a state-owned company in Buenos Aires, Argentina, during 2023 were included. Incomplete or poorly completed instruments were excluded.

An ex Profeso instrument was implemented, consisting of 15 closed-ended questions that inquired about the sociodemographic profile of the respondent (eight items), their experience in seeking health care (three items), and their interaction with nursing staff (four items). The instrument was developed based on a quick review of the literature, drawing on similar studies.

The instrument was transferred to Google Forms survey management software and sent via email and instant messaging applications to workers who met the inclusion criteria. At the end of the collection, the responses were exported to a Microsoft Excel database and analyzed using the free version of Infostat software.

Data analysis was performed using descriptive statistics (univariate analysis), calculating the absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies of the variables of interest evaluated. Graphs and tables were prepared to facilitate understanding of the data.

The study is considered low risk given its observational and anonymous nature. Written informed consent was implemented, participation was emphasized as voluntary, and confidentiality in data handling was ensured. No personal or identifying information was requested.

RESULTS

Forty TTT and NB individuals participated, mostly between the ages of 20 and 29 (32,50 %), who identified as trans women (55,00 %), with secondary education (45,00 %), health insurance (45,00 %), and who had identified since childhood with a gender different from that assigned at birth (47,50 %). The complete data are shown in table 1.

|

Table 1. Characterization of the sample |

|||

|

Variable |

Categories |

n |

|

|

Age |

20-29 |

13 |

32,5 |

|

30-39 |

12 |

30 |

|

|

40-49 |

7 |

17 |

|

|

50-59 |

8 |

20 |

|

|

Self-perceived gender |

Trans woman |

22 |

55 |

|

Transgender male |

15 |

37 |

|

|

Non-binary |

3 |

7,5 |

|

|

Level of education |

Primary |

10 |

25 |

|

Secondary |

18 |

45 |

|

|

Higher |

12 |

30 |

|

|

Healthcare |

Public |

12 |

30 |

|

Social security |

18 |

45 |

|

|

Private |

10 |

25 |

|

|

Discovery of self-perceived gender |

Childhood |

19 |

47 |

|

Adolescence |

16 |

40 |

|

|

Adults |

5 |

12 |

|

|

Social expression of self-perception |

Childhood |

5 |

12,5 |

|

Youth |

26 |

65 |

|

|

Adults |

9 |

22 |

|

|

Total |

40 |

100 |

|

92,50 % of respondents reported considering or having undergone hormone therapy, although only 62,50 % have undergone sex reassignment surgery.

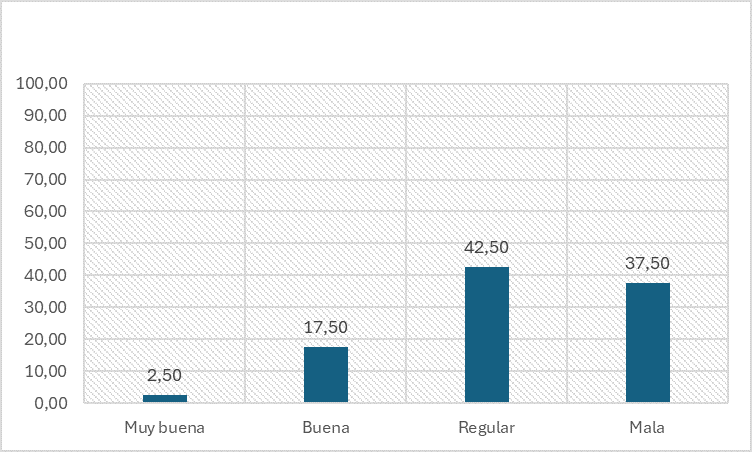

When asked about their experience with health services, most respondents rated it as fair (42,50 %), followed by poor (37,50 %) (figure 1). Negative experiences were mainly associated with ignorance and lack of understanding of the specific health needs of TTT and NB people (57,50 %), while others reported dehumanizing treatment (42,50 %). These data are reflected in the report that 75,00 % mentioned that their gender identity was not respected during health care.

When asked about communication with nursing staff, 45,00 % said they felt uncomfortable or nervous, 22,50 % perceived disinterest, 12,50 % said they did not know how to explain why, and 20,00 % did not experience any difficulties. Despite these data, 40,00 % reported always experiencing discrimination and stigmatization, 57,50 % sometimes, and only 2,50 % reported never having experienced it. Likewise, 17,50 % reported always experiencing mistreatment and 75,00 % sometimes.

77,50 % of respondents said that nursing staff should ask TTT and NB people how they would like to be addressed. This shows that TTT and NB people value and find it important to be asked about their self-perception and which pronouns to use when interacting with them. This preference reflects a growing awareness and respect for gender identity and the importance of using appropriate and respectful language.

Figure 1. Characterization of the experience in the health system.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study consistently reveal the multiple barriers faced by transgender and non-binary people when interacting with health services, particularly with nursing staff. Despite regulatory and social advances in relation to the rights of gender-diverse people in many countries, the experiences of TTT and NB people continue to be marked by ignorance, discrimination, and inadequate healthcare systems.(11,12)

In this sample, composed mainly of young people (aged 20 to 29), transgender women, and those with secondary education, there is unequal access to essential health practices, given that the conditions in which care is provided do not necessarily guarantee dignified or respectful treatment. In particular, the fact that 75 % of respondents reported that their gender identity was not respected during healthcare reveals a profound structural failure in the training and awareness of healthcare personnel.

The negative or fair assessment of the healthcare experience among the majority of respondents is mainly associated with a lack of awareness of the specific health needs of this population and dehumanizing treatment, which affects almost half of the respondents. These findings are in line with previous research that has identified a systematic lack of training on sexual and gender diversity in healthcare training programs.(13,14) In turn, the discomfort and nervousness reported by nearly half of TTT and NB people during interactions with nursing staff reveal a professional relationship marked by tension and mistrust, which can hinder continuity of care and clinical follow-up.(8)

Likewise, the high percentages of people who reported experiencing discrimination and mistreatment reflect not only individual practices but also structural patterns of exclusion within the health system. Such practices directly impact the right to equal access to health care, promoting a hostile environment that can lead to avoiding medical consultations, postponing treatment, or resorting to informal care, with the risks that this entails.(15)

A key finding of the study is the express demand by the majority of participants that nursing staff actively consult on the correct way to address TTT and NB people. This result reaffirms that respect for self-perceived identity and the correct use of names and pronouns are central elements in providing humane care. Far from being a formality, this practice has profound implications for people’s subjective and emotional validation and should be understood as part of the ethical and professional standard of healthcare.(16,17)

The persistence of experiences of discrimination, together with the desire for more respectful and sensitive practices, poses a double responsibility: on the one hand, to critically review the curricula of health-related degree programs to incorporate mandatory content on comprehensive health care for LGBTI+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex) people; and on the other hand, to promote continuing education opportunities for practicing professionals, with a focus on human rights, gender perspective, and diversity.

Although limited in sample size and geographical representation, this study provides relevant evidence for understanding the experiences of TTT and NB people in the healthcare system. It is essential to develop public policies that ensure respect for gender identity in all areas of the healthcare system and to move towards inclusive, person-centered models of care that are committed to equity and social justice.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study show that trans, transvestite, and non-binary people face significant barriers in accessing and receiving quality care in health services, particularly in their interactions with nursing staff. Most of the experiences reported were average or negative, with ignorance, lack of understanding of their specific needs, and dehumanizing treatment standing out as the main sources of discomfort. Disrespect for gender identity, along with perceptions of discrimination, stigmatization, and mistreatment, reinforce the urgency of reviewing current practices.

Despite this picture, opportunities for improvement were also identified: most participants appreciate being asked how they wish to be addressed, which underscores the importance of recognition and respect for gender identity in every clinical encounter. These findings highlight the need for ongoing training for nursing staff with a focus on human rights, diversity, and gender, as well as the implementation of protocols that guarantee safe, respectful, and non-discriminatory care. Promoting a more inclusive healthcare culture will not only contribute to the well-being of TTT and NB people, but will also strengthen the quality and equity of the healthcare system as a whole.

REFERENCES

1. Sherman AD, McDowell A, Clark KD, Balthazar M, Klepper M, Bower K. Transgender and gender diverse health education for future nurses: Students’ knowledge and attitudes. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;97:104690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104690

2. Hanna B, Desai R, Parekh T, Guirguis E, Kumar G, Sachdeva R. Psychiatric disorders in the U.S. Transgender population. Annals of Epidemiology. 2019;39:1-7.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.09.009

3. Lee SR, Kim M-A, Choi MN, Park S, Cho J, Lee C, Lee E. Attitudes Toward Transgender People Among Medical Students in South Korea. Sex Med 2021;9:100278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2020.10.006

4. Ley identidad de género, Ministerio de Justicia de la Nación, Argentina, Ley 26.743, 2012. https://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/195000-199999/197860/norma.htm

5. Fundación Huesped. Ley e Identidad de Género y acceso al cuidado de la salud de las personas trans en Argentina, 2014. Disponible en: https://huesped.org.ar/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/OSI-informe-FINAL.pdf

6. Zalazar V, Arístegui I, Cardozo N, Sued O, Rodríguez AE, Frola C, Pérez H. Factores contextuales, sociales e individuales como barreras y facilitadores para el acceso a la salud de mujeres trans: desde la perspectiva de la comunidad. ASEI. 2018;26(98). https://doi.org/10.52226/revista.v26i98.22

7. Tollinche LE, Van Rooyen C, Afonso A, Fischer GW, Yeoh CB. Considerations for Transgender Patients Perioperatively. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2020;38(2):311-326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anclin.2020.01.009

8. Pelle CD, Cerratti F, Giovanni PD, Cipollone F, Cicolini G. Attitudes Towards and Knowledge About Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients Among Italian Nurses: An Observational Study. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2018;50(4):367-374. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12388

9. Derbyshire D, Keay T. Nurses’ implicit and explicit attitudes towards transgender people and the need for trans-affirming care. Heliyon. 2023;9(11):e20762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20762.

10. Lim FA, Hsu R. Nursing Students’ Attitudes Toward Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Persons: An Integrative Review. Nursing Education Perspectives. 2016;37(3):144-152. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000004

11. Bhatt N, Cannella J, Gentile JP. Gender-affirming Care for Transgender Patients. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2022;19(4-6):23-32. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9341318/

12. Boyd I, Hackett T, Bewley S. Care of Transgender Patients: A General Practice Quality Improvement Approach. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(1):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10010121

13. Poteat T, German D, Kerrigan D. Managing uncertainty: a grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84:22-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019

14. Grant JM, Motter LA, Tanis J. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, Washington, DC, 2011. http://arks.princeton.edu/ark:/88435/dsp014j03d232p

15. Canova-Barrios CJ. Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness among HIV-Positive People from Buenos Aires, Argentina. Invest Educ Enferm. 2022;40(1). https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.iee.v40n1e11

16. Schneider JT, Kimmel SJ. Caring for Transgender and Gender Diverse Clients: What the Radiological Nurse Needs to Know. Journal of Radiology Nursing. 2023;42(3):279-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jradnu.2023.03.005

17. Rider GN, McMorris BJ, Gower AL, Coleman E, Brown C, Eisenberg ME. Perspectives From Nurses and Physicians on Training Needs and Comfort Working With Transgender and Gender-Diverse Youth. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33(4):379-385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.11.003

FUNDING

The authors did not receive funding for the development of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Erika Silvia Stolino.

Data curation: Erika Silvia Stolino, Carlos Jesús Canova-Barrios.

Formal analysis: Erika Silvia Stolino, Carlos Jesús Canova-Barrios.

Fund acquisition: Not applicable.

Research: Erika Silvia Stolino, Carlos Jesús Canova-Barrios.

Methodology: Erika Silvia Stolino, Carlos Jesús Canova-Barrios.

Project management: Erika Silvia Stolino.

Resources: Erika Silvia Stolino.

Software: Carlos Jesús Canova-Barrios.

Supervision: Erika Silvia Stolino.

Validation: Erika Silvia Stolino, Carlos Jesús Canova-Barrios.

Visualization: Carlos Jesús Canova-Barrios.

Writing – original draft: Erika Silvia Stolino, Carlos Jesús Canova-Barrios.

Writing – review and editing: Erika Silvia Stolino, Carlos Jesús Canova-Barrios.